Bimonthly Membership Meeting

Wednesday, August 5, 2020

7:30 PM -- 10:00 PM

Virtual Zoom Platform from Pittsburgh, PA

At least eighty-four individuals participated in 3RBC's August meeting - the club's first-ever virtual meeting, held on the Zoom platform. The meeting featured Tessa Rhinehart whose talk was entitled, "Eavesdropping on Birds."

3RBC President Sheree Daugherty called the meeting to order at 7:30pm. She then made announcements.

• Sheree thanked the members for their strong support and loyalty throughout the Covid-19 emergency. She noted that, even though the club had neither held a meeting since February, nor hosted any outings since March, the club has not only maintained its members, it has actually gained a few! Even in the face of this good news, Sheree noted that, however impressive, convenient, and effective the Zoom platform may be, she looked forward to being able to meet face-to-face and get out and bird together again. She then announced that tonight's format would be a bit different: she would briefly summarize the information usually provided by the club's various officers, with a presentation by Tessa Rhinehart to follow. She added that, for those who are interested, more details usually contained in the officers' reports will be available on the club's social media page, its website, and in The Peregrine. She reminded everyone to pay attention to their emails, since Tom Moeller would be communicating future meeting news and other developments. Finally, thanks were sent out to Tessa Rhinehart, Michelle Kienholz, and the indispensable Tom Moeller for helping the club get up to speed with the Zoom format.

• Editor Paul Hess sent along news that bird behavior would be a theme in the next Peregrine, in both Sheree's President's Message and Tom Moeller's "Observations" column, which was inspired by the return of Cedar Waxwings to his yard after several years' absence. His column will discuss that species lifestyles and behaviors, with his customary fine photographs illustrating. The upcoming issue will also feature part two of Frank Izaguirre's report on his and his wife Adrienne's trip to Canada. Check it out to resolve Part One's cliffhanger: Did they see the owl?

• 3RBC Vice President Mike Fialkovich's full listing of recent bird sightings for Allegheny County is available in its entirety in The Peregrine. Reader's will note that several really interesting migrants passed through this spring. Sheree provided highlights as follows: a pair of Virginia Rails returned to Harrison Hills Park, where they were confirmed breeding - a first for the park; an American Avocet was seen at Riverfront Park on the Southside in July; two Black Vultures were spotted in Fox Chapel (one was wing-tagged); some hybrids were seen - a Brewster's Warbler in Frick Park in April and a Lawrence's Warbler in Deer Lake Park in May and June; adding to unusual warblers, a Prothonotary Warbler lingered at Boyce-Mayview Park till mid-June; a window strike victim - a Swainson's Warbler - was collected Downtown in early May; Summer Tanagers appeared, a female in Gibsonia and a male in Frick Park in May; finally, a pair of Blue Grosbeaks were seen in Imperial in July and August. Sheree again reminded everyone that Mike's complete list is available in its entirety in The Peregrine.

• Sheree told the viewers about a great opportunity to participate in a citizen science project that can be done by individuals - an important caveat in the Covid era. The Allegheny Bird Conservation Alliance partners - Pittsburgh Parks Conservancy, Western Pennsylvania Conservancy, and Carnegie Museum of Natural History - are working with Allegheny GoatScape to remove invasive plants, restore native plants, and monitor bird and habitats in the Clayton Hill area of Frick Park. The partners would like to see birders accessing the area beginning now and through September and adding eBird observations for the restoration areas to monitor the effectiveness and outcomes of the restoration effort conducted in that area of the park. Please visit 3rbc.org for more information on this valuable project and how you can help.

• Regarding outings, Sheree re-stated the club's position: due to the pandemic emergency and the potential danger to leaders and attendees, there are no outings planned for the foreseeable future. The club will resume its outing schedule as soon as it is safe to do so.

• Sheree noted that the club's next meeting - also on Zoom - will be Wednesday, October 7th. The meeting's featured speaker will be our own Frank Izaguirre, who will present "Field Guides and Environmental Thinking." Frank will answer the question: What do field guides do? He says that field guides are politically consequential texts that persuade the way people conceive of animals, plants, and the many other objects they catalogue. Tom will keep everyone informed of times and details.

President Daugherty next introduced the evening's speaker Tessa Rhinehart, whose program, "Eavesdropping on Birds" describes a process created at the University of Pittsburgh, which uses computer-based "ears" to survey species on a scale that would be impossible for field birders to achieve. She is part of the Pitt research team that developed this new technology.

Tessa has achieved a significant milestone as the chief author of her first peer-reviewed article in a scientific journal. "Acoustic Localization of Terrestrial Wildlife: Current Practices and Future Opportunities" reviews worldwide research in the "eavesdropping" techniques. You can read it in the Ecology and Evolution journal at

https:// tinyurl.com/Tessa-article.

A research programmer in the Pitt Biological Sciences Department, Tessa is pursuing a master's degree in Pitt's Graduate School of Public and International Affairs, majoring in energy and environment.

A Pennsylvania native, Tessa discovered a love for nature while growing up in the hills around Bradford. She graduated from Swarthmore College in 2017 with degrees in biology and mathematics. At Swarthmore she received the Heinrich W. Brinkmann Mathematics Prize and the Leo M. Leva Memorial Prize for her achievements in biology.

Tessa does not spend all of her hours in a lab. In her free time, she is an avid birder and enjoys volunteering with the Kiwanis Club of Sheraden.

Tessa began her program by tell everyone that she is a birder who cares about preserving and restoring bird populations, which we are losing at an alarming rate. In order to do that, we need to know a lot about where they are. Her job focuses on developing large scale automated survey methods, that combine autonomous acoustic recorders with computer programs that can identify the species we hear making sounds on the recordings. Her presentation dealt with why we do these surveys, and how they work.

She explained that animal surveys are essential in several ways: they help us understand the impacts of global change, they help us monitor population trends, and they identify ways to prevent declines.

Surveys begin by going someplace out in nature, say a national park, a restored wetland, even someplace like Duck Hollow, and identifying what's there. Breeding bird surveys are a good example of such wildlife analyses.

Most of these types of surveys are done by direct observation: someone goes out and writes down what species they see. But in Tessa's scientific fields - conservation and preservation - a revolution is taking place. Researchers are using automated sensors to survey wider areas than ever before. They are using tools like motion sensors, camera traps, satellite and airborne imaging, autonomous audio recorders, and auto-sampling environmental sensors. All these devices have massively increased the amount of data that can be collected. What makes them even more powerful, these sensors measure biodiversity while using automated analysis techniques that understand and parse the outputs of the sensors.

Tessa's lab combines autonomous sound recorders with computer programs that tell or predict which sounds are captured by the recorders.

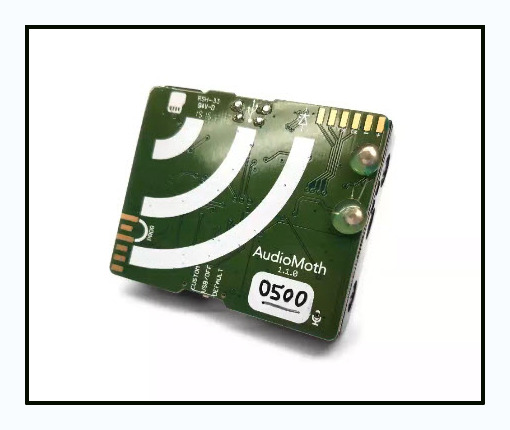

She showed pictures of the recorders which are small and enclosed in a simple Ziplock bag. They can be left alone in the woods for months, all the while gathering valuable data without any human input. The recorders can pick up pretty much the same thing that a human standing in that spot could hear: animals, like birds and frogs; environmental sounds, like wind and rain; human sounds, like planes and cars; and all the other sounds of that location.

Tessa explained that sound is a really effective way of surveying certain groups of species, especially birds. She related that upwards of 90% of birds detected by humans while surveying are detected by their sounds - the bird calls - that they make. Given this, sound is a very effective way of surveying bird species.

Tessa's laboratory focuses on using autonomous acoustic recorders instead of human surveys for four reasons:

First, autonomous recorders are more cost-effective for covering large spatial or aural scales. They provide greater coverage and more bang for your buck. Recorders can also be put up in advance of a time-crucial event, such as a migration wave or weather front. For a relatively modest investment - basic recorders cost about $50 - researchers can gather thousands of hours of data.

Second, recorders match the effectiveness of traditional human surveys for many species and conditions, but they substantially outperform humans when it comes to surveying difficult species or events. They are especially effective in surveying nocturnal species, such as owls or nightjars. Additionally, recorders can be used to capture events for which humans are poorly suited, such as species that are rare or that don't vocalize very frequently, or live in difficult environments. The recorder is eternally patient and provides researchers with a better chance of sampling the species they are studying. Recordings can also identify the timing of a species arrival at a particular location, for instance, a migration wave. Plus, recorders can survey for species that are shy and unlikely to be observed if they become aware of the presence of humans. Though not designed for this purpose, recorders can also detect human-generated sounds, such as gunshots, which locate illegal hunters, or chainsaws, which can pick up illegal logging operations.

Third, recorders can perform surveys in places that humans have a difficult time accessing. They can be placed in remote locations and gather invaluable data for months on end. Solar panels can power them and allow deployment for long periods of time without human maintenance.

Fourth, researchers can treat acoustic recordings like museum specimens, creating a library of sounds that can be accessed for many, many years thereafter. Recordings are a permanent record of a soundscape, preserving an area's full aural biodiversity at a particular moment in time. Unlike human surveyors, recorders also provide a verifiable record that can be checked by any number of experts.

Tessa went on to explain that recorders and technology are not designed to replace human biologists, ecologists, and field workers. There is nothing that can replace a human's curiosity, or the ability to holistically synthesize an entire landscape, and notice many, many things at the same time, all the while formulating new hypotheses.

As for how this is all done, Tessa showed slides of the actual recorders used, essentially a circuit board with a digital storage device, powered by three AA batteries, all stuffed in a Ziplock bag.

This mighty mite of technology can record 150 hours of sound on a single charge. The tiny recorders, fully outfitted, cost less than $100 each; more than 10,000 have been made and are at work. Tessa and her collaborators have deployed about 2,800 of these vigilant listening devices across the United States, and as far as away as Canada and Borneo. Sites where recorders are deployed are carefully chosen. Breeding bird atlas locations are especially good, because the recordings can be compared to the work of expert human surveyors. Recorders are set to record in intervals totaling about three hours a day, starting about a half an hour before dawn. On this schedule, a typical recorder will last about two months before its data storage device needs to be emptied and its batteries replaced. After the field season is done the recorders are retrieved, and the analysis work begins.

This mighty mite of technology can record 150 hours of sound on a single charge. The tiny recorders, fully outfitted, cost less than $100 each; more than 10,000 have been made and are at work. Tessa and her collaborators have deployed about 2,800 of these vigilant listening devices across the United States, and as far as away as Canada and Borneo. Sites where recorders are deployed are carefully chosen. Breeding bird atlas locations are especially good, because the recordings can be compared to the work of expert human surveyors. Recorders are set to record in intervals totaling about three hours a day, starting about a half an hour before dawn. On this schedule, a typical recorder will last about two months before its data storage device needs to be emptied and its batteries replaced. After the field season is done the recorders are retrieved, and the analysis work begins.

These many hours of recordings are not listening to by humans; instead, an automatic sound identification algorithm identifies the sounds in the recordings. Summarizing a long and complicated process, the sounds are converted to spectrograms, sometimes called sonograms or spectrographs. These visual representations of bird songs are then analyzed, using sophisticated machine learning techniques.

But how does the program know what bird each particular sonogram represents? A human birder listens to the sounds and literally teaches the program that this particular sonogram belongs to that particular bird species. Once the program is taught, it can take it from there! To date, several bird vocalizations have been added to the algorithm, and it can accurately identify them by their sonograms; but there remains much work to do!

Tessa then concluded by reminding the listeners that technology - even amazing technology like she described - is not a substitute for the excellent eyes and ears of human birders. Her project's goal is to work out all the kinks in the process so that autonomous recorders can accurately identify birdsongs and, thereby, board locations. Also, to provide invaluable support to ecologists, ornithologists, and conservation biologists. When this point is reached, these researchers will have a powerful tool for conservation and bird preservation.

Following the presentation, President Daugherty moderated several questions that had been typed into the Zoom chat feature by listeners, which were answered by Tessa.

Sheree then thanked Tessa for her excellent presentation and adjourned the meeting.

— prepared by Frank Moone on 10-5-2020